English Version

Вы находитесь: Археология.PУ / Персональный сайт Л.С. Клейна

In this section: Annotations | Autobiography

By Leo S. Klejn, 1.03.2009

Born on 1 July 1927 in Vitebsk, then Byelorussian SSR, in a Jewish family of intelligentsia, atheistic and radically russified (already for two generations before me in the family the first language was Russian, and before it Polish). My background was of the upper stratum of the society. Before the Revolution both grandfathers were capitalists: one was a factory-owner, the other a merchant of the first guild to which the richest merchants (2 – 5 %) of Russia belonged. In the Civil war my father who had graduated from Warsaw Imperial University was an officer in the Denikin’s Volunteer Army. By the end of the war he was in the Red Army. Of course, he was never a member of the Communist party – neither was I

I studied at a Byelorussian high school and at a music school (piano). When the Patriotic war broke out in 1941, my parents were called up as physicians and went to the front; the rest of the family (myself and my grandparents and younger brother) were evacuated to Yoshkar-Ola, Mary SSR (behind the Volga). There I worked on a kolkhoz (collective farm), and finished the eighth and ninth grades of Russian high school. Then, at the age of 16, I went to the front as a civilian. In 1944 I was stationed on the Third Byelorussian front, a unit of military builders, and with this unit I went from Smolensk to the German border.

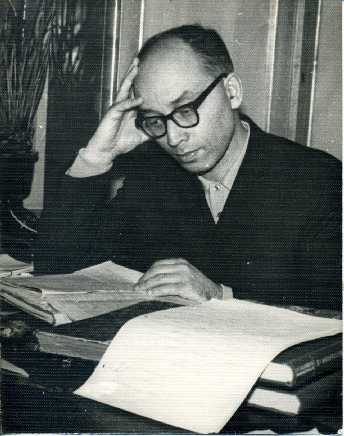

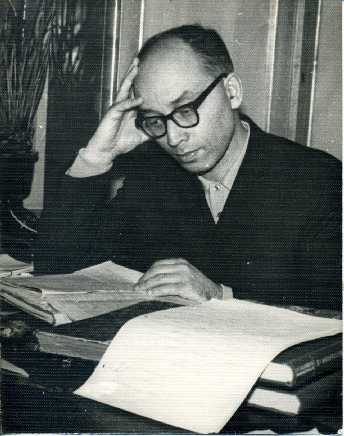

In the spring of 1950 the fourth year student of the department of archaeology Lev Klejn has delivered a paper in the session of academic counsel IIMK Ac. of Sc. of USSR with a sharp criticism of N. Ya. Marr’s teaching (half a year before Stalin’s criticism). The photograph is of the student on the day the paper was delivered in the session hall of IIMK

Zoom

|

The last Stalin’s years were tense for Lev Klejn – four times he forced his way into post-graduate studies. His father was linked to the “case of wrecker physicians”. It was at this time his friend Michail Devyatov (now professor at the Academy of Arts) drew his portrait (charcoal, 1953)

Zoom

|

In the autumn of 1944, probably due to a near missile explosion, my myopia became accompanied by choreoretinitis of both eyes (inflammation of the retina and the optic vascular system) and I was threatened with the prospect of blindness. I was sent with a hospital train to the district of Smolensk, the very place from where our advance had begun. There, once the acute period of the disease was over, I attended Roslavl’ railway technical school to complete my secondary education. Poor eyesight barred me from any profession that involved driving, but I was accepted at the school for another profession (building railway wagons). However, I was there for only a year.

After the war I was reunited with my family and settled down in Grodno where by this time my father had become the head of a hospital and my mother had become a surgeon and head of the city’s emergency unit. There I passed examinations as an “extern” (without attending lectures) and entered the department of language and literature of the Grodno Pedagogical Institute.

After a year of study (1946) I enrolled for a correspondence course at Leningrad University; a year later I moved there (and left Grodno Pedagogical Institute). For some years I studied at University simultaneously in two different faculties: in the historical faculty (in the department of archaeology, under the guidance of Prof. M. I. Artamonov, the Director of the Hermitage Museum) and in the philological faculty, under the guidance of Prof. V.Ya. Propp). I graduated with distinction, in 1951.

As I had entered the University whilst unfit for military service (due to poor eyesight), I did not go through military officer training – my friends were enlisted as reservists into the artillery. However the state of my eyes improved and upon graduating I was pronounced fit for certain sections of military service. So as to offer me the rank of officer (in common with my friends from university) those responsible, taking into account my ability with languages, enlisted me as a military translator. I was able to fulfil the physical requirements for these were not so high for officers as for the rank and file. (Much later, in 1966, at the age of 39, I was called up for two months of officer training courses).

After graduating I worked for half a year as a bibliographer at the Library of the Academy of Sciences, in Leningrad. Over the next years I worked as a teacher in various high schools in Leningrad, then of Volosovo community (in the district of Leningrad), then in Grodno. From 1957 to 1960 I pursued post-graduate studies in archaeology at Leningrad University. I then delivered lectures at the same department (for an hourly wage and gratis) and in 1962 was accepted onto the staff of the department as an Assistant Professor. In 1968 I was promoted with the Candidate dissertation (the first of two promotions in Russia, equal to Ph.D. in the West). The origin of Donets Catacomb-grave culture. In 1976 I became a Docent (approximately Associated Professor, Reader). My first scholarly work was published in 1955, my first monograph in 1978 (when I was already 51). I have participated in a number of archaeological expeditions (in the forest belt of Russia and Byelorussia, but mainly on the steppes of the Ukraine and surrounding the river Don); the last 5 seasons were as head of the expedition (till 1973). After this I continued to be a member of expeditions but as head of student training; the head of the expedition was another archaeologist. The excavations included ancient Russian towns, Bronze Age and Scythian/Sarmatian barrows.

In archaeology I concentrated upon the Neolithic and Bronze Ages; the Scythian, Sarmatian and Slavic cultures; and theoretical archaeology.

Over the whole of my career I held views that were considered unorthodox - deviating from the accepted line of Marxist-Leninist scholarship. The authorities also frowned on my contacts with foreign scholars (some of my earliest work was published abroad). It was probably owing to my reputation that my closed relatives were persecuted (my father was drawn into the ‘case of wrecker-physicians’; my younger brother was expelled from the Communist party and lost his job in Byelorussia for statements against the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968). My national origin was also significant. For all these reasons my career was stalled and my main works remained unpublished.

In the 1960s Klejn has become an Assistant Professor at the department of archaeology. This was time when he was concerned with Catacomb-grave and Tripolye cultures and with the debate on the Varangians

Zoom

|

However while the country adhered to the policy of détente, my activities were tolerated. My situation changed sharply when by the New 1980 year Soviet troupes entered Afghanistan and the policy of détente was abandoned. Sakharov was exiled to Gorky, and in Leningrad liberal professors began to be arrested. As the official slogans proclaimed that there were no political prisoners in the Soviet Union, for everyone arrested some criminal offence had to be invented.

In March 1981, upon the initiative of the KGB, I was arrested and accused of homosexual behavior. The state prosecutor demanded 6 years imprisonment and 5 years’ banishment from civil society – this would entail losing my residence permit in Leningrad. Yet, despite the guidance of the KGB, the court trial fell to pieces, and I was sentenced to three years of imprisonment. After my appeal this sentence too was repealed. The case was handed over to a new inquest, and after a fresh trial I was sentenced to year and a half. As I had already spent a year and a month in prison this left just five months to serve in a labour camp. It was customary in our judicial system to hand out such a sentence in place of an acquittal.

Recognition came by the age of 70. l. S. Klejn in the 1990s. Photo by Yu. Yu. Piotrovsky

Zoom

|

Upon my release from the camp I was stripped of my scholarly degree and title (in violation of several laws). For many years I had no job, despite the fact that I was officially registered for work on the labor exchange and that there was (officially) no unemployment in the country.

When perestroika began I published a series of essays in the journal Neva (1988 – 91) and then a book (The world turned upside down, 1993, the German version 1991) in which, with the original documents of the trial, I demonstrated the role of the KGB in the case. Not only were there no denials but my former investigator addressed an open letter to the Editor of Neva (then also the Chairman of the special Committee of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on civil rights), in which he admitted that my account of events was correct. He also admitted that he was forced by his superiors to arrest me and to make the case despite poor evidence. The letter was published but the sentence was never retracted. However, soon the logic of revising the case became irrelevant, since the law according to which I had been convicted was abolished.

As a result of these publications, containing sharp criticism of the Soviet regime, I was elected a deputy to the First congress of Democratic organizations of the USSR (1989, Leningrad). I was also a participant of the intelligentsia club Leningrad tribune. Throughout these years I continued my research work and to write books and articles.

Aside from archaeology I dealt in this period with two other disciplines – classical philology and cultural anthropology. In the first I studied a subject that borders folklore-studies and archaeology, namely Homeric problem. This was a textual criticism, and historical and statistical analysis of the Iliad. In cultural anthropology I was engaged upon a theory of culture (evolution and the change of cultures) and a subject on the verge of sexology and criminology - deviant behavior. I was moved toward these themes by my sojourn in prison and camp and my conviction for homosexuality. The result was a series of articles and three books.

From 1987 I have received the retirement pension. From 1989 at times I have again given lectures at Leningrad University and, since I received the opportunity to go abroad, from 1990 I taught as a Visiting Professor at many universities of Europe: First at the Free university of West Berlin, then at Durham university (England), and later at Vienna and Copenhagen universities, I have also delivered lectures in London, Cambridge, Oxford, and at 6 other universities of Great Britain, 4 universities of Sweden, 4 of Spain, 2 of Norway, 2 of Denmark.

Conceiving the life of the country, the discipline, and his own. L. S. Klejn in 2008 when the memoirs were written (published in 2009). Photo by Damir Gibadullin-Klejn.

Zoom

|

In my homeland I obtained my degrees and titles anew. In 1993 I defended my doctoral dissertation (senior dissertation in Russia) with the book Archaeological Typology at the Institute for the History of Material Culture (IIMK) of Russian Academy of Sciences (awarded unanimously). In 1994 joined the staff of the department of philosophical anthropology where I started teaching cultural anthropology. From 1995 I also taught this subject at the ethnological faculty of the new European university at St. Petersburg – university that was founded upon my initiative. In 1997 I was elected a permanent Visiting Professor at Vienna University. In September 1997, then aged 71, I left St. Petersburg University and in 1997/1998 I finished giving regular courses at the European University. Yet separate courses of lectures were delivered at the department of archaeology of the St.Petersburg University until 2005.

After I left these teaching posts I continued to give courses of lectures abroad –in Slovenia, Finland, and in the academic year 2000/2001 at university of Washington, Seattle. Shortly after my return to Petersburg, I was diagnosed as having prostate cancer. I underwent an operation in 2001, but in 2004 the cancer was found to have returned. I have been under treatment ever since, and so far I am fortunate in that the spread of the disease has slowed down. Meanwhile I work as a freelance scholar at home and occasionally deliver my papers in public. The freedom from teaching has allowed me to concentrate on research and writing. The results can be seen in half a dozen monographs and some hundreds of articles.

All in all I have published 14 monographs (including translations the total is 21) and ca. 400 articles in scholarly journals and collections, some of them are under my editorship. My first monograph (Archaeological sources, 1978) was republished in 1995 in the series Classics of archaeology. At present 4 books and two dozens of articles are in print, and several others are on my desk. Since the summer of 2008 I also have a column in the Russian scholars’ paper Troitsky variant.

My adopted son Damir (a Tartar, from Yoshkar-Ola) is not legally registered (because he settled at my home not as a child, but after the school), but he has taken my surname. He graduated from Stiglitz Industrial-Arts Academy, then pursued post-graduate studies, and is now an employer. He is married with an infant son. Damir and his family live with me. My brother, a professor of history and pensioner, emigrated to U.S.A. together with his wife and sons (my nephews). One of them is a lawyer, the other mathematician and programmer.

As to awards, I have war medals, and the Higher Anthropological School of Moldova awarded me the title of Dr. Honoris Causa after I delivered my lectures there.

March 1, 2009.

Back to top

Author’s notes to autobiography

I compiled my autobiography according to administrative conventions: a brief outline of the major steps in life placed in chronological order (born…, entered…, finished…, etc.) and in a nondescript style, indicating the evidence that is frequently required (of nationality, party membership, kinsfolk, awards, convictions). In foreign countries the format of a CV (lat. Curriculum Vitae – the description of life) is more usually not chronological but thematic (name, surname, place of birth etc.) and is usually more detailed – with indication of exact dating, numbers, official denominations, full lists. This is almost equivalent to our Russian “anketa” (questionnaire, form) attached to the autobiography.

An official needs a form: every evidence is in its proper place, and you cannot hide or hush up any unpleasant evidence. The reader takes more readily to an autobiography: in it he expects to find more of the psychology of the personality and the logic of its development.

To write autobiography was not difficult to me: from schoolboy to pensioner there have been so many cases where I had to present it that it was always in my personal dossier; and so it gradually expanded – over some seventy years. To be sure, the choice of detail and the emphases were changed according to the requirements of those to whom it was addressed and and according to the situation of the country. For instance, under the Soviet regime there was no sense in writing too frankly about the social status of my ancestors, it was better in referring to my social origin to simply state “from employed personnel” - further details only by special request. The questionnaire was quite another matter (only if the wording of the questions allowed it, could one omit unfavourable evidence).

Yet such a life story is too dry and sparse. Yes, it gives some general impression of the personality. But from a public man (the writer, scholar, artist or politician) the reader expects something more. He expects a biography (and, especially, an autobiography) to help him better understand the making of this person and his social position, and to shed light upon the motives behind his activities and creations. This is why the genre of the interview is so popular. As a rule the interviewer puts just those questions that are avoided in the autobiography. The same questions are raised at meetings between a writer (or other luminary) and his audience. These questions also appear in readers’ letters and in correspondence with friends (usually published posthumously).

Newspapers and journals have more than once published interviews with me, and I have also received readers’ letters. Thus I anticipate certain question that may arise and I shall try replying them in advance.

1. Ethnicity. What does it mean to be a ‘radically russified Jew’? Is he a Jew or a Russian? The point is that by many indices (lingual and cultural), but mainly by self- conception I am a Russian. Although I have five languages, I do not number any Jewish language among them, neither Yiddish, nor Hebrew; and my native language is Russian. This is the only language, of which I am the absolute master – it is the language in which I think. I have no adherence to Judaism – I am an atheist, as were my father and grandfather (and their wives).

Yet, I am a Russian of Jewish origin. I do not renounce my ancestors. I have some reasons to be proud of them and some reasons to be ashamed. The same is true of everyone. I have not “deserted” to another ethnicity: it was my ancestors who underwent assimilation, and so I was assimilated from birth. For me to become a Jew “anew” would imply changing my ethnicity. In my opinion the majority of Russia’s Jews are of this sort – the exception being the small group that gathers around the synagogue). In contrast to the Jews of Israel (indeed a separate nation, with their own particular ethnos), Russian Jews are something like a caste of the Russian people, like the Cossacks or the Pomors (White Sea coast-dwellers). Indeed, only anti-Semites now speak with a Jewish pronounciation (they mimic Jews with an accent lost by the Jews themselves).

This question is important for people because it is upon Jewish ethnicity that national character is supposed to depend; as well as national solidarity, and the defense of interests of national hearth (Israel, Zion). Let us consider all three of these claims.

1) What is it that is specifically Jewish that I have inherited from my Jewish ancestors? If one excludes the outlook (that is generally held in common by the population of South Europe) modern Jews are distinct in their choice of preferable professions and by some features of national character – they are especially fond of their children (there are no Jews among waif children); they are enthusiastic for learning; and hate hard drinking. Yet none of these features is exclusively Jewish, they are inherent to many native Russians as well as are Biblical names. The difference is only in the extent of the distribution of these features.

For instance my name is Lev – it is a purely Russian name (from the Greek Leon stems the Slavic Levon (in Byelorussian Lyavon), in Russian this became Lev (pet name Löva). After the time of pogroms in which Lev (Leo) Tolstoy defended the Jews, this name became a very popular Jewish name. Yet I was called Lev not after Leo Tolstoy, but in memory of my uncle Leon who died before my birth. Patronymics are common in Russia. My patronymic from birth was Stanislavovich for my father, according to Polish custom (he was born in Warsaw), had three names: Samuil-Solomon-Stanislav (two Biblical names, one Polish). At home and at work he was called by his Polish name, and from this I received my official patronymic. At 16, on receiving my passport I changed it to Samuilovich, from a feeling of self-esteem: to have hidden my Jewish heritage at a time of worldwide persecution would have felt mean. This however did not involve a change of ethnicity. Then, as now, I thought of myself as a Russian and was classed in my documents as a Jew.

2) National solidarity or mutual aid among Russian Jews is strongly exaggerated by non-Jews – from jealousy (from tales of worldwide Jewish plots). In reality the mutual aid of Jews is manifested only in the extreme situations brought about by persecutions (as in every persecuted minority), and even this is not invariably the case. Jews themselves know its real worth. The Jews are as disparate and egotistical as any other group in our country (social connections are much weaker than in other countries of Europe and than in America). In my long life I received no more help and support from Jews than from any other people – friends and colleagues. Nor, with the exception of my parents, did I receive more help from relatives than from others. And from a certain world organization of Jews I received nothing at all, for of course such organization exists only in the over-heated imagination of anti-Semites.

Among my close friends and pupils the proportion of Jews is no larger than among the surrounding city population. Among those who have lived for long periods at my home there were no Jews at all. My adopted son is Tartar, his wife Azerbaijani. Yet all of us are, in practice, Russians.

3) As to the interests of the national hearth, my national hearth, my homeland is Russia. Its interests and its problems are mine.

Towards Israel I am full of sympathy and respect like many in Russia, regardless of origins. It is good to know that the people expelled from its homeland two thousand years ago and dispersed have created anew its state on the same territory; that during the life of one generation it transformed the desert into a blooming world; smashed superior military opposition and successfully defends its right to live by European and world norms and standards. Yet at the same time I understand the local Arabs who lived there for nearly a thousand years and for whom the Jews are newcomers. It hurts me to see two peoples destroy each other, - and that the local Arabs choose a hopeless strategy of permanent war (and inner faction), instead of building on their remaining territory a state that compete with the Jewish one in bringing pleasure to their inhabitants and to its neighbors.

However I do not personally long for Israel: this is a very interesting and rich country, but not mine.

2. Marxism. There is a contradiction in my works between those in which my allegiance to Marxism is declared and those in which Marxism is criticized and rejected. Mostly the two sides of this contradiction coincide with a division between times, and this is clear to everyone. Yet in my case such division is incomplete.

Under the Soviet regime the declaration of loyalty to Marxist ideology was in our country unavoidable, and many formulations and quotes from classics of Marxism-Leninism were a kind of conventionalities, some tribute to customary norms of decency, and the obligatory formulas and quotations from the classics of Marxism-Leninism wit which every work was laced were, so to say, the red bows around the subject that demonstrated the author’s loyalty. Owing to my social origins, education and upbringing I was not imbued from youth with Marxism as a philosophy and methodology. However I understood that if I wanted to teach and be published, if I was to bring my thought and the results of my research to the community, then I would have to dress myself in Marxist cloth.

Most of the guardians of ideology were neither well-versed in scholarship nor in Marxism. In these conditions one could air even non-Marxist and non-Soviet ideas so long as one used the language of Aesop; in other words, one had to write in such a way that the perceptive reader could read between lines. I catalogued fourteen varieties of this skill in my book The phenomenon of Soviet archaeology (1993, in Russian; Germ. transl. 1997), in the Chapter “The language of the Sphinxes”.

On the other hand I strived to find in Marxism at least some areas of sense so as to draw not from the vast swathes of Marxist dogma but just from these small oases. From the classics of Marxism I tried to select quotations concordant with my ideas (the classics were so voluminous that you could find quotes for every purpose). For instance, I argued that Marx and Engels held prehistory to be a non-political discipline!

Basically, some Western scholars considered me to be a defender of Marxism, but an unusual defender – it was possible to discuss scholarly problems with him! Some of my opponents among Marxist-dogmatists whom I caught in ignorance of Marxism regarded me as a fellow Marxist-dogmatist, but of a higher class, i. e. well-read in Marxist Scriptures. But it was impossible to swindle the main corpus of our guardians of ideology: they scented an adversary in me and did not count me as their own. Evidence of dissent was found not just in my main ideas but even in minutiae. For example, the Secretary of Party Bureau of the Faculty criticized my references to Marxism in my works on the grounds that I had avoided the conventional double-barreled Soviet term ‘Marxism-Leninism’.

After the collapse of Soviet power one could write and speak freely, and I was able to explain that I perceived Soviet orthodoxy as a utopian propagation of socialism (paradise on earth). Marxists distinguished Marxism from other utopian teachings by its scientific character, but in itself science does not grant us the truth. Marxism therefore remains as much utopian as many other forms of this belief. Marx was a competent economist, but he was basically wrong when he saw in man only a junction of economic relations; man is also a biological being with ineradicable properties: care of his own children and kinfolk at the expense of others, love of his own milieu and animosity to strangers and strange customs, etc. Marx was completely wrong in his estimation of the perspectives of capitalism and the bourgeoisie, of the role of working class, and the like. The attempts to establish socialism, beginning with the first phalansteries and ending with the bloody reign of Pol Pot in Kampuchea, invariably terminated in revolts of the benefited masses and in devastation. I speak of socialism as the first stage of communism. Western socialism is quite another matter. Marxism is a theory that has refuted by experiment – and not just once.

However in in the new era I did not reject all of the attainments of Soviet scholarship nor even all Marxist positions. Materialistic convictions remained in me (and I admit the force of materialist ideas also, likewise atheism. Socio-economic analysis remains for me a valuable tool in the historiographical study of the discipline. Dialectics remains a strong principle of cognition in the study of a number of complex phenomena, and I frequently make use of it. It is not correct to consider Marxism as simply an agglomeration of nonsense and gibberish. Valuable accomplishments in philosophy and political economy have been achieved through Marxism. The fact that Marxism has itself been discredited does not imply that these achievements are annulled. Abusus non tolit usum.

3. Atheism. It is usually not the custom in an autobiography to make one’s relation to religion explicit. However, nowadays many artists, writers and politicians and workers of culture proudly profess their religious orthodoxy. In former times atheism was in our country something taken for granted in an educated and politically loyal man. But today the state inclines towards fusion with the church, and Communists have become devoutly pious – they cross and star themselves, as in Voyinovich’s old anti-utopian Moscow of 2042 (only half a century earlier than in his book). Indeed, our situation is like that of Germany after the Thirty-year war: cujus regio, ejus religio. While there is an atheist in the Kremlin, temples are crushed, and the whole country blasphemes. While there is a hypocrite in the Kremlin, everyone light candles. In these conditions I decided to note in my autobiography that I have grown up in an atheistic milieu and remain an atheist. This is not a challenge or an expression of Fronda. It is a belief.

Whatever you may say, atheism is a worldview that befits the scholar. Science is incompatible with the belief in miracles. The scientist and the scholar cannot and should not believe in supernatural forces. They should recognize only those forces that are either recognized by science or that might in principle be recognized by science. Otherwise he is in the wrong place. The result of his experiment cannot be cannot be thought to alter depending on whether or not he offers a candle to God. The scholar cannot rule out inferences from his theory if they contradict religious dogma. It is the dogma that should give way if the science refutes it. And as we know many religious dogmas have had to give way. True, not all of them –religion maintains some. Yet the general rule is: science advances, religion recedes.

For modern believers gods are no longer anthropomorphic or zoomorphic beings sitting on celestial thrones, but invisible spirits, abstract forces, all-knowing and omnipotent. The essence of religion is their veneration in prayer and ritual. It is thought that these must bring success in life and redemption from misery. Those who are personally convinced of the importance of religion, in essence personify in these invented beings (their real existence was never proved) their own - and traditional - hopes, morals and standards of conduct. Religion is based on sheer personal psychology: for many people it is easier to dare doing something, if they imagine they have behind them the support of certain strong figures, and likewise it is easier to give up something, if they imagine the disapproval of the same figures. - Gods or saints. For the sake of serving this illusion (necessary to many) the whole enormous industry of churches is created; and as states are interested in the support of traditional norms, usually they like and support their church (and this feeling is mutual).

Of course, beside their principal function, churches have accomplished many useful things: increased literacy, stimulated philanthropy, maintained morals in everyday life, developed urban architecture. Yet the evil they have done has not been negligible: via confessions they stimulated national and religious dissent, inspired religious wars, burnt heretics, butchered those of different beliefs, and in every way possible discouraged the development of science. Usually popes and monks preach asceticism rather than acquisitiveness, but the church itself accumulates colossal riches.

Atheists should not be inferior to the clergy in their activities. In America psychoanalysts have already deposed priests from the role of confessor. This is not the best change, but it is a symptom. I hope that in general mankind will take notice of psychologists rather than popes. This will be much better for sound self-appraisal, general temperance and for the purse.

4. Sexual orientation. The question of my sexual orientation arises from the the facts of my biography, and it is left in the autobiography without being clearly answered. Well, these facts are known even without my autobiography for the question has been discussed in the press.

On the one hand, I wasn’t married and I was charged with having committed homosexual acts (illegal under the Soviet regime) and convicted, and the conviction was not annulled after the collapse of the Soviet power. On the other hand, the case was initiated by KGB and was conducted under the guidance of this institution (proofs of this were published in my articles in Neva and in my book The World Turned Upside Down (1993) and no denials were made), though sexual cases were not the responsibility of the KGB. I have not admitted the charge, and my former investigator disavowed the case in public (in an open letter to Neva).

Both sides of the contradiction can be reinforced. On the one hand, in my one-room apartment there lived young men who helped me over many years, now one, now another. The last of them became my adopted son. (One respectable memoirist possibly has this in mind when he writes that around Klejn whom he believes to be a “model of the Russian intellectual” there were all the time some lads were present). On the other hand all of them married, have families and continue to have the best of relations with me - as do their parents.

On the one hand I have published two books on the problem of homosexual orientation and prepared one more. One journalist (who presents himself as a self-confessed scandal-monger) holds up this fact as an undoubted proof of my homosexuality. He abuses me in print with an unprintable term from prison slang. One of my published books, which he did not read, he attests as my autobiography and an exposition of my homosexual adventures. Well, this is a strange blunder for a journalist: the book of my memoirs is still in print and it contains no mention of my homosexual adventures.

On the other hand, it was natural for me to become interested in the problem that served as the pretext for my expulsion from scholarship. I do not propagate homosexual orientation in these books, but I strive to grasp its essence - and I criticize homosexual subculture for being as harsh as homophobic behavior. As distinct from apologists of homosexuality I hold it to be a pathology in a biological sense, but I understand that in the socio-cultural sphere the boundaries of norms were set by different societies, each with different norms (cf. biological and cultural norms in culinary – to what extent is diet natural and to what extent is it the product of custom!).

In no one of my printed work did I classify myself as homosexual and in no one did I refute this possibility.

If I would dispel the mystery and declare my true sexual orientation, I would be certain to fall into an inconvenient situation. In any case some of my readers would not believe me. If I declared my orientation to be normal, many readers would regard this as an evasive lie. If I declared myself to be homosexual, more would believe it (people are always inclined to believe the more scandalous version), but it would also appear to be a publicity trick. Moreover, it would then also be thought: so he lied in court to save himself, how is it possible to believe anything he says? In summary, in any of these scenarios I would be forced to go beyond a simple statement and to present proofs and facts, and this would be indecent and ridiculous.

The fact that a clear division between homosexuals and heterosexuals exists only in the notions of average men adds to the complications: in fact a scale is built with gradual passage from one end to another, and people are placed on the scale in different cells (professor Kinsey held there seven such cells). So am I asked to seek the cell that fits me – in public? In a fair society this classification is done in private with a physician.

My position on this question is as follows. In the courtroom I denied only those particular deeds for which I was charged. And evidently I was convincing enough that though the case was brought by such a powerful organization it fell to pieces and the investigation was forced to resort to falsifications (as the court was forced to admit). As to the general question of my supposed homosexual inclinations, this was not - even then – seen as worthy of judicial inquiry. Moreover, I would have contested any desire on the part of the state to intrude upon my private life. Today, I still maintain that this is not the business of the state; nor is it within the sphere of interests of a normal society.

When, at public meetings, readers pass me slips asking about my true sexual orientation, I answer that this is only of real interest to those who have sexual intentions towards me. Only he (or she) has to know if I am a suitable partner or not. So this is something that would be appropriate within personal relations, but, even then, it is not an inquiry that should be pursued with direct questions. And, taking into account my old age, it really makes no sense at all

Sexual orientation seems to the reader important as soon as he connects with it some predilections and effects in the creation of a person. Such reflection is of course possible, especially with respect to the creation of writers and artists. But, as to the scholars, if a scholar’s sexual orientation finds reflection in his scholarly production, then this reflects badly on his methods. I hope that even in my works on homosexuality my own sexual orientation, whatever it might be, is not reflected at all.

5. Self-appraisal. Throughout my career I dared to solve very prominent and central problems, and I also initiated important studies. But questions concerning theory and method were in our country always seen as a prestigious business that was the prerogative of the aristocracy of scholarship. Thus all the time I had to defend my positions in debate, and to group around me supporters and disciples. As my background was unpromising (a Jew, from the “former” people, not a member of the Party) I had to struggle for my place in scholarship – first simple for a place, then for a prominent place, for leadership. This, quite naturally, provoked people, especially adversaries, to regard me as a jumped-up upstart, excessively exaggerating his own importance.

Well, the painstaking accuracy of my lists of attainments, as witnessed in my autobiography and record-keeping, may give an unpleasant impression of excessive self-conceit and on megalomania. But, with equal care, I also recorded criticisms, both of my work and of myself.

Now, some allowance can be made for my age. I am at that age when summing up is customary. Yet I must confess, I have had this habit already for a long time.

When I was still a young assistant at the department of archaeology, our dean V. A. Ezhov who was my almost my exact contemporary (he was from the next student-year), complained about recurrent trouble arising from my participation in scholarly conflicts. “With you one cannot be bored”, he sneered, always awaiting from me (not without grounds) annoyances to the faculty. Finally he came up with the idea that I should keep a permanent account of everything that was written about me in the press, both at home and abroad. I should, so to say, collect a dossier on myself, and be ready to present it upon request. He suggested that the dossier include not only printed statements but also opinions expressed in private letters (especially by foreigners) about my works – in order that should the occasion demand it, I might say, “Here is what was really said: . . . “ Of course, he understood that to pretend on privare letters was too far. Yet firstly they were looked over by the censors (at that time, this applied to everyone’s correspondence, including foreigners); secondly there were only a few quotes about my work; thirdly they remained in my own dossier, at home.

I established such a dossier, and later could evaluate its advantage: I always collected the reactions to my works – so as to judge their effect and for the purpose of debate.

My colleagues poked kindly and not so kindly fun at what they saw as my self-conceit, if not self-exaltation. M. Vakhtina published in Stratum a parody on self-exaltating Klejn. I myself played with these jokes (cf. my Debate on Varangians) – though some my colleagues perceived this in earnest.

A.A. Formozov, now late, wrote in the Preface to the collection in honor of A.D. Stolyar that Klejn had from the beginning “declared himself great”. Indeed? Where have I declared this? Perhaps “imagined” or “thought”, but not “declared”! I reproached him in a letter:

“When have I ever said or written anything like that? Even if I thought it, I could not say it. “Great” was my student nickname, a mock antonym of my surname (Klejn is small in German). My friends called me this, especially Sasha Grach. Recently this epithet has appeared in the writings of my pupils, this time in earnest (Preface to the collection in my honor, in which as you will understand, I I was not a contributor). From pupils this may be excusable”.

After 80 it is still possible to look sensibly and boldly into the future. Photo by Damir Gibadullin-Klejn

Zoom

|

To my longstanding sparring partner V.F. Gening (also now late) I frankly wrote that in my opinion he was not suited to studies in theory. Offended, he wrote back: “You are too infatuated with self-admiration, with you abilities, especially theoretical. Frankness for frankness – be afraid of this maniacal obsession!” I have retorted this with the message: “The head of the psychological seminar which I mentioned in Kiev conducted an examination of my psychological characteristics. His conclusion: underestimation of his own abilities is inherent in the investigated. Strange. I would rather have agreed with you. But he forced me to participate in many long and boring tests”.

It seems to me that some overestimation of one’s abilities and of the importance of one’s activity is useful. It adds drive and concentration. It prompts work. At my old age I have come, I think, to a sound estimation of my contribution to scholarship. I am not inclined to exaggerate it, but I don’t want to minimize it either – from modesty, or in more decent wording, false modesty

Modesty is in general a relative concept. Questioned about his opinion of a staff officer whom had been assigned to him Suvorov replied: “Well, a nice officer, shy and modest in battle”. There are immodest professions: writer is one such; professor is another. If you are that intent on modesty, stay at home in the dark.

Modesty in taking is one thing, modesty in giving quite another. All my life I was modest in taking – I have acquired neither professorial apartment (I live in one-room garsonnière), nor dacha, nor car. Yet I was immodest in what I offered to people.

Summarising my life I see that some my attainments are considerable within our discipline. I promoted the development of theoretical archaeology; introduced a new understanding of the place and nature of archaeology; elaborated concepts of classification and typology and methods of ethnogenetic studies and how to recognize migrations; discovered Indo-Aryans in the Catacomb-grave culture; ordered the system of notions about Normans in the ancient history of Russia; advanced a hypothesis recognizing proto-Hittites in Baden culture etc.; worked out a new understanding of Homeric epic. That is a fair amount.

At the same time I see that many my ideas have not been taken up and developed, for instance: my theory of communicative development of culture, and my strategy of system grouping, my idea of the division of labor between archaeology and prehistory etc. This is partly because our discipline was unprepared to perceiving of my ideas, and partly because I was unable to adequately explain them.

I am aware of having been known in my country and in the world, and a third of my published works are in foreign languages, but my main monographs remain untranslated into English and do not exert influence upon the worldwide development of our discipline. I am known throughout the world but only in the narrow world of archaeologists and not always for my main works. With this proud and sad conscience I depart.

В начало страницы

По вопросам, связанным с размещением информации на сайте, обращайтесь по адресу: a.eremenko@archaeology.ru . Все тексты статей и монографий, опубликованные на сайте, присланы их авторами или получены в Сети в открытом доступе.

Коммерческое использование опубликованных материалов возможно только с разрешения владельцев авторских прав. При использовании материалов, опубликованных на сайте, ссылка обязательна © В.Е. Еременко 1999 - настоящее время

Нашли ошибку на сайте? Сообщите нам! Выделите ошибочный фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter

|